I’ve been climbing for five years now, and it’s been an incredible journey. I first started with indoor bouldering because I loved the problem-solving aspect — and the social side of it too. It was a sport I could do alone and never feel bored. Five years in, I still have so much to learn.

Lately, my partner and I have been getting into lead climbing and exploring outdoors. That’s opened up a whole new world — endless places to visit and routes to try. It’s exciting, but also overwhelming in the best way.

I wish learning and growing were always fun. But when your ego gets involved, you face mental challenges on top of the physical ones. And that’s not just in climbing — it applies to anything where you're trying to improve.

On Ego and Grade-Chasing

In climbing, I often find myself obsessed with the idea of sending and the grade of each climb. In my head, I only felt strong if I sent a route that I believed was beyond me. Some might say that’s okay — that grade-chasing gives you a goal, a reason to train harder. But I realized it mostly feeds the ego. And when you fail, it hits harder.

I started noticing that I wasn’t just disappointed after failing — I was hesitant even to try. I got angry. I remember one time my partner took me to a climb because he believed I could send it. But when I fell on the first move, I was overwhelmed with shame and frustration. I lashed out, wondering why he brought me there. Was he just trying to show off? Was he pressuring me?

The truth is, he wasn’t pressuring me at all — he genuinely believed in me. But I couldn’t see that. All I could see was how the climb made me feel, not the climb itself. That’s when I knew something was wrong.

It got worse on my projects. I would feel anxious even before I touched the wall. Eventually, it reached a breaking point — I found myself arguing with my partner and blaming him for how I felt. That moment made it clear: chasing grades and trying to prove something was stripping the joy out of climbing. It wasn’t about movement or exploration anymore. It was about ego — and ego was exhausting.

On Fear

Fear of falling is another huge mental battle. It’s biological — a survival response. Falling can feel like dying, even if we’re actually safe. It takes time to retrain your brain.

But I used to get frustrated with myself for being scared. I’d spiral into this loop of thoughts:

“I don’t know if I can do this move.” → “I might fall.” → “I’m scared.” → “I don’t want to feel scared.” → “I can’t fall here.” → “I’m stuck.” → “I’m getting pumped.” → “Why are you scared? Are you a pussy?”

Telling myself “Don’t be scared” only made it worse. That mindset led to disappointment and self-hate. What I’ve learned is that the first step is allowing myself to feel scared. It’s normal.

I remember staring at a route — a grade 19 — hands shaking, heart racing. I knew the fall was clean, but I still froze. Sometimes I even cried mid-route, stuck between wanting to move and being terrified to fall. At the same time, this harsh voice in my head would kick in:

“This is such an easy route. The fall is safe. If you bail, it means you gave up. Prove you’re strong. Prove you don’t quit. Prove you’re a winner — not a loser.”

There was also a time I believed the only way to feel safe was to avoid falling completely. I told myself:

“If I’ve assessed that a fall is unsafe, I must be in real danger — so I can’t trust myself to move forward.”

But that thinking only made everything scarier. It left no room for trust — not in my gear, not in the process, and not even in myself. Avoiding every fall isn’t realistic, and conflating fear with danger only holds you back.

Overcoming fear isn’t about pretending risk doesn’t exist. Some falls are objectively unsafe, and walking away is valid. But not all fear signals danger. Learning to tell the difference is part of the process.

Being afraid doesn’t make you weak. Being fearless doesn’t automatically make you brave. Fear exists to protect us — and that’s a good thing.

On Tools That Help

Overcoming the fear of falling — and all the mental spirals that come with it — wasn’t about ignoring my feelings. It was about building habits that helped my brain believe I was safe.

A few tools made a difference:

- Risk assessment: Before climbing, I’d ask myself honestly — is this fall clean? Is the bolt placement good? If the answers were yes, I reminded myself I was physically safe.

- Fall practice: This helped the most. The first time I deliberately let go mid-route, I was terrified. But nothing happened. I fell, I swung, and it was fine. Doing it again and again allowed my nervous system to recalibrate. Each time I practiced falling, my body started to trust what my brain already knew - this is safe

- Breathing techniques: I practiced deep, conscious breaths when I felt overwhelmed. It helped me stay grounded, especially when I wanted to retreat or panic.

These tools don’t erase fear, but they give you ways to respond to it — and that’s everything.

On Self-Trust and Self-Love

The more I reflect, the more I see that growth requires self-love.

When I’m scared, I need to be gentle with myself. When I fall, I need to recognize the effort I gave and allow myself another chance to try. I need to encourage myself instead of tearing myself down.

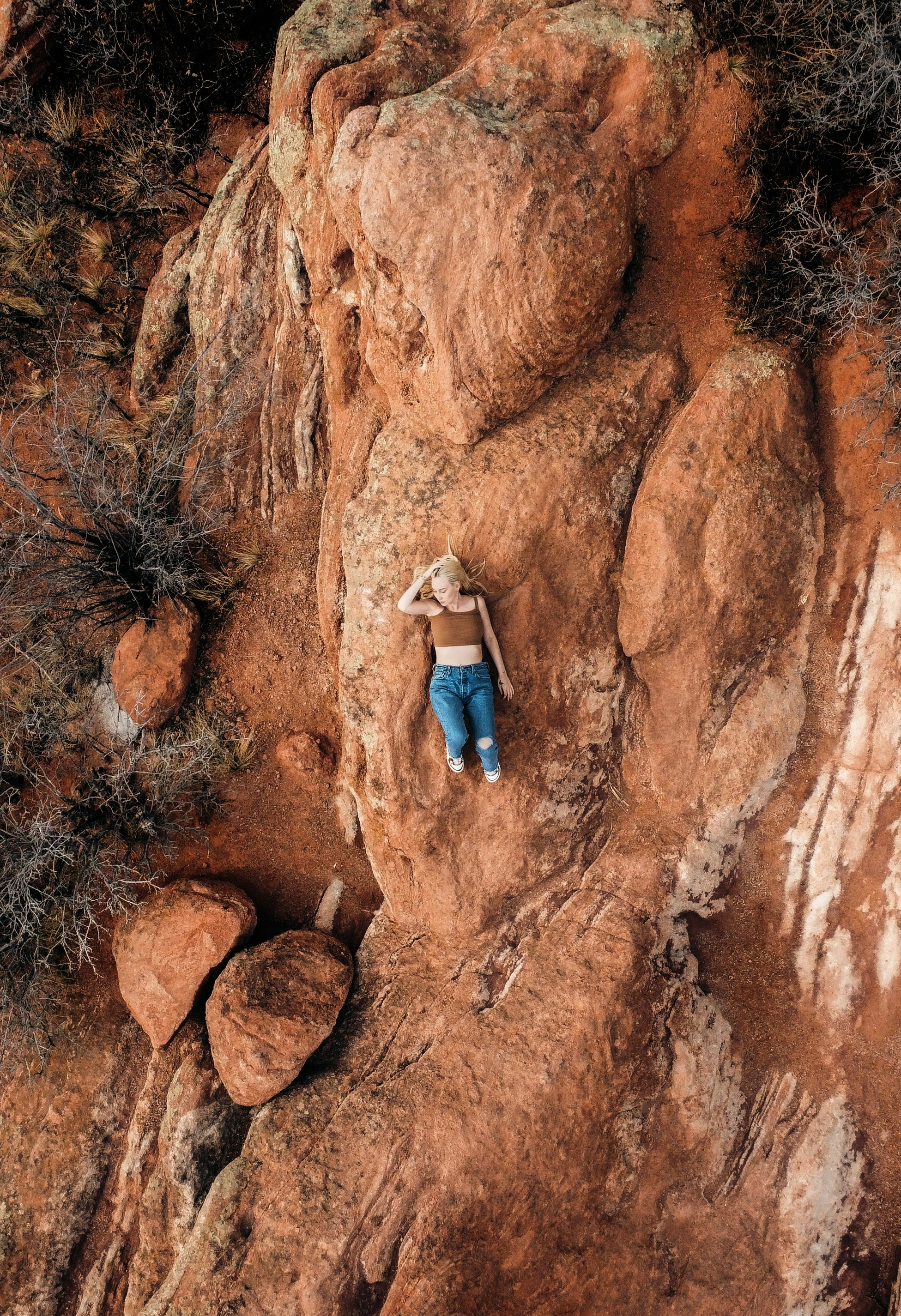

I’m learning to climb not to prove anything — but to experience, explore, and connect with something deeper.

Some days, I still catch myself chasing grades or feeling frustrated. But I’m quicker now to notice it. I pause. I remind myself that how I feel on the wall matters more than what I send. I want to climb with curiosity, not pressure. To enjoy the movement. To celebrate effort over outcome.

This is what I’m working toward now:

Climbing from a place of love — not fear, not ego.